Two weeks ago, in honor of the game-changing Madoka Magica’s 10th anniversary, it was announced that a sequel to 2013’s Rebellion movie had begun production, reuniting Madoka’s entire lead production staff, including the long-absent but pivotal creative voice of writer Gen Urobuchi. Even though the anime landscape is overflowing with twisted magical girl subversions eight years later, fans are still hungry for a shocking resolution to the darker storyline posed by the Madoka movie trilogy—soon to be a quadrilogy at least. That once-edgy idea of “mahou shojo for adults” has certainly cemented into a stronger and more established genre today, but as a wise man once said, “To understand the future, we have to go back in time.” Or was that Pitbull?

My point is that I’m not here to talk about Madoka today. Instead, its revival has made me nostalgic for those bygone years when the Dokes’ wild success had not yet been imitated to the point of monotony, back when its release was met with irritation from a subset of hipster otaku who were quick to insist that its adult “innovations” on a children’s genre were old news—you’d know that if you were a serious mahou shojo fan. Snobbery aside, the nerds did have a point. Magical girl subversions aimed at an adult audience not only existed before Madoka, they were becoming a hot trend as early as 2004, when My-HiME, Rozen Maiden, and other genre hybrids sought to bridge the gap between childlike, feminine flights of fancy and the complex speculative horror that their late-night audiences craved. Far from being failed experiments that aired before their time, these anime quickly became underground hits, franchises that all continue in some form or another to this day. But if any of them could fairly be called an ancestor of Madoka, it would have to be the one helmed by Madoka’s own director, Akiyuki Shinbo. Its own four-word title even sits atop Madoka’s on Shinbo’s curriculum vitae: Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha.

Seriously, if you were to compare just the first episodes of these distant cousins, you might conclude that Madoka was ripping Nanoha off completely. After a few placid scenes with 9-year old Nanoha’s picturesque family, where she laments her inadequacy compared to her parents and older siblings, Shinbo’s trademark atmosphere of dread takes over the episode. Oblique, fish-eye camera angles and clinical, washed-out lighting press pervasively on your nerves, even throughout scenes where the music and acting remain bright, and Nanoha’s daily life with her two flawlessly supportive (and obscenely wealthy) best friends seems otherwise hunky-dory. It’s not long before this peace is interrupted by the arrival of an adorable wounded creature—an alien boy in ferret form named Yuuno, who turns Nanoha into a magical girl after she rescues him from certain death. Her new duties as the youngest defender of earth are certain to distance Nanoha from her family and friends, and her fascination with another—seemingly villainous—magical girl named Fate Testarossa drives a greater wedge between the naïve Nanoha and more pragmatic heroes protecting the galaxy above her. Beat for beat, this beginning is absurdly familiar in its tone and focus. It’s hard to deny that Urobuchi took inspiration from Nanoha specifically when director Shinbo hired him to write Madoka several years later.

But while the two stories start out damningly similar, their paths quickly diverge to paint a more edifying picture of how magical girl anime would evolve, and how Nanoha would learn to run so that Madoka could fly. Unlike its darker descendant, Nanoha does not chug forward with a propulsive or cohesive vision from the jump. Early episodes of the show could be scattershot and frivolous, with a modest but indelibly uncomfortable level of fanservice (an upskirt shot here, a hot springs vacation there) that hard-panders to the genre’s least respectable niche in ways that we would not see reprised by Madoka. Mercifully, the underage cheesecake does get thrown out early in season one, and once the story begins taking itself seriously, Nanoha’s hidden darkness took on a completely different form than I expected.

After farting around with monsters-of-the-week (and her enigmatic rival Fate) for a while, Nanoha’s seventh episode takes a hard right turn from fantasy to sci fi, when a city-wide magical disruption demands the attention of the Time-Space Administration Bureau. The whiplash is real when we cut to the bridge of a massive spacecraft above our planet, bustling with astro-naval officers we’ve never seen before. Chrono, Lindy, and the other crew members immediately broaden Nanoha’s humble story, teleporting the elementary schooler away from her bland best friends and boring family. Nothing of value is lost in the trade; those characters were already struggling to carry their own weight, and they will only flicker faintly in the rearview mirror for the rest of the show, as the franchise realizes its true audience. That’s not to say that the TSAB officers are much less bland in personality, but the galactic stakes they carry give them far more complicated things to talk about. The only characters that actually matter are other magical girls, because Lyrical Nanoha distinguishes itself from its family-friendly contemporaries with baby steps compared to the capital-D Darkness we expect from post-Madoka mahou shojo—now the magical girls fight each other more often than they band together to fight monsters, but Nanoha’s reasons for this focus on human combat are far more optimistic than fans who started out with the more cynical Madoka might expect.

Nanoha and Fate are young children with limited perspectives, but as magical girls, they have theoretically limitless power, making them hot potatoes for older characters with more grown-up concerns to juggle. The Bureau knows it would be easier to arrest or annihilate Fate before her doomed quest to gather magical power for her Evil Mom’s approval destroys the known universe, but Nanoha refuses to cooperate with such cold-blooded protocol. She’s just a little girl who sees another girl suffering and wants to help her. Since the genre around Nanoha has shifted from fantasy to sci fi, she begins to understand that her magic wand, Raising Heart, is a piece of technology, no different from her flip-phone in its pure and simplistic intelligence. Nanoha’s optimism drives her to use Raising Heart as a unique tool for communication with Fate on the battlefield instead of destruction, in the same way that e-mail still connects Nanoha to friends and family far away. There are no Faustian bargains or malevolent cursed wishes like the kind that forced Madoka Magica’s victims to turn on one another for survival. The “magic” of Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha does not stem from an emotional connection to an otherworldly power, but one’s own personal fortitude, mental strength, and an undying optimism that even mankind’s devastating inventions can be used for the betterment of all and the salvation of the weak.

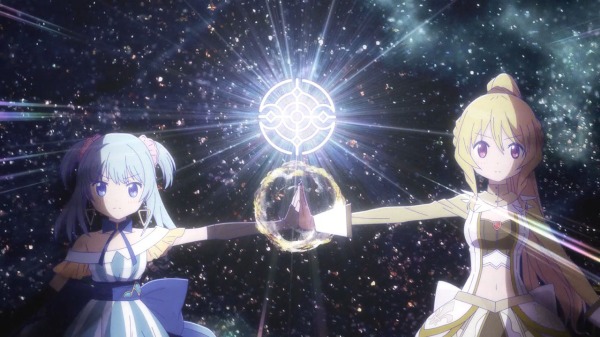

Over its first two seasons (and possibly beyond, though that’s as far as I’ve gotten), Nanoha’s focus on communication, curiosity, and acceptance of technology as a neutral tool for good or evil takes it about as far from Madoka as you can possibly go. Futurism reigns as we learn about how each magical item is “programmed” like any other piece of technology, to be abused or misunderstood by we fallible and impure meatbags, but ultimately decoded and innovated on for the sake a brighter future. Since all the “villains” are other misunderstood little girls being manipulated by cruel adults or corrupted technology, Nanoha can use her aptly named Raising Heart to defragment their scrambled souls, expanding her world in the process to include more magical new friends. No matter how dire their circumstances might be, and no matter how close the Time-Space Administration Bureau might come to deploying the nuclear option on Nanoha’s misunderstood future friends, the darkness that pervades Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha only comes from without, never within the girls themselves. With enough patience and research, any problem can be solved and any soul can be saved.

It’s an optimistic perspective for an “adult” magical girl anime, especially compared to what we’ve come to expect from that genre today, but this optimism is easier to accept in a story where all the heroes remain children. By the 2010’s, most magical “girls” in post-Madoka anime were magical teens on the cusp of womanhood, with a greater potential for twisted motivations that blur the lines of good and evil between them in battle. But for Nanoha, Fate, Hayate, and all their familiars and friends, it doesn’t matter to them that their magic wands are technically weapons of mass destruction instead of candy-colored friendship dispensers. Their hearts remain pure, their bonds remain true, and the citywide destruction they endure while firing off their pink space lasers is just another adventure for their scrapbook. It’s definitely a “dark” magical girl anime, aimed at adults, but Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha never seeks to interrogate themes of girlhood, womanhood, or the true weight of a wish your heart makes. Making friends and doing the right thing is easy when you’re 9 years old, even if your side hustle is blowing shit up with magical space weapons.

I enjoyed my time with Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha, but despite its greater focus on combat, technobabble, and tragedy than your average season of Pretty Cure, it ultimately feels closer to the family classics of its genre than the late-night horrors its legacy would eventually conjure up in Madoka Magica. And it feels almost a thousand years removed from Madoka’s imitators like Yuki Yuna is a Hero or Day Break Illusion, which bristle with so much bleeding edge and sanguine surrealism that they can be downright unpleasant. I’d much rather watch Nanoha than the more mean-spirited Madoka descendants, but that’s sort of like saying I’d rather eat a kid’s meal burger than a burnt-black steak. We’re assuming the best option, a meal meant for me that’s not overdone, is not on the table. Even in the darkest moments of Lyrical Nanoha’s plot, we know that Nanoha and her friends will come out the other side just as hopeful and spirited as always. Even if Madoka copied Nanoha’s pilot script paper and snatched up several elements of its story structure, they feel so distantly related in the evolution of the dark magical girl genre as we know it today.

By the end, Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha (and its second season, Nanoha A’s) feels like one last dream before dusk, a pleasant—but still just weird enough—fantasy you have after succumbing to a power nap too late in the day. There were fun moments, rejuvenating feelings, and maybe even a whisper of true inspiration in its sci fi take on a children’s genre that was just starting to follow its fans into adulthood. However, it’s easy to forget Nanoha’s optimistic innovations when you awake to see that dusk has fallen upon you, and a long night of Madoka imitators has clouded over its faintly shining star.

Special thanks to leafbladie for commissioning this review!